Joyce Carol Oates is a masterful storyteller who creates multi-dimensional characters who draw relentlessly upon the reader’s emotions with her powerful capacity to use words to bring struggling souls to life.

With this astonishing talent, she warms, disturbs, and even frightens the reader who begins to live enmeshed and lost in the worlds of each of her characters.

What the characters cannot escape from – both their promising and threatening experiences – the reader, too, ensconced in such literary magic, cannot escape from either.

Novels

1. Them

In this remarkable novel Oates engages us in deep longings for love, challenges of Detroit City life, and stolen dreams.

Loretta

Loretta’s children grow up in the threatening city of Detroit’s poverty, racial strife, poor education, and impermanent homes. Jules, the oldest, and Maureen, next in line, are the focus of Loretta’s world. Her other children are peripheral and neglected.

Loretta knows nothing of how to understand her children’s emotions, misreads their struggles, can barely keep up with her own serious mistakes in life choices, yet remains loyal in her own confused but particular devoted way, at least to Jules and Maureen.

“Her name was Loretta. It was her reflection in the mirror she loved, and out of this dreamy, pleasing love, there arose a sense of excitement that was restless and blind—which way would it move, what would happen?…squinting into the plastic-rimmed mirror…seeing inside her high-colored, healthy, ordinary prettiness a hint of something daring and dangerous. Looking into the mirror was like looking into the future; everything was there, waiting” (p. 3).

“‘ Hey, Loretta!’

‘Yeah, I’m coming.’ Her voice came out harsh and sounded of the drycleaners and the street, but it was not her true voice; her true voice was husky and feminine.” (p. 4).

Loretta has a brother whom we meet early on when they are young; he vanishes and returns. She gets on with him though their emotions often flare:

“She was sitting upright, her shoulders sightly raised, tense, ‘Last night, that was so stupid! It was cruel. You egg him on, and he says things, and you get mad at him, it’s like lighting a match and dropping it, and why?'” (pp. 7, 8).

Oates gives Loretta powerful words that often create insinuations about her family members as she grows up, and later on, she does the same as her own children grow up.

Loretta’s relationships with men reveal her lack of self-worth, her trials to find others who might care for her and don’t. She questions the meaning of her life and life itself. Her dialogue tells us about her search for truth and reality as harsh as it may be.

“What was the truth?” (p. 14) about the plight of her parents and later about herself as a parent with difficult husbands?

“She spoke in the fatal, final, partly satisfied singsong her mother and other women in the family had used, as if they’d already come to the end of all the worst possibilities and were waiting there for the men to catch up” (p. 15, 16).

Oates tells us about Loretta’s fears and terrors by relating her dreams.

“she slept…and seemed to be stumbling around in rooms she’d never seen before, taking hold of the helpful arms of people, staring into their eyes but finding no center to them, no iris… But it was not dream of terror; she felt only exhausted and wet with sweat, overcome. A heavy leaden warmth lay up her…Then there was a loud sharp noise…She woke at once, already screaming, the scream mangled and inaudible. It was stuck back in her sleep, deep in her mind” (p.26)

Oates has Loretta reveal the theme of going crazy that threads its way throughout the book in the lives of those who surround her.

“Loretta forced herself to look carefully around the room, her room. She had to figure out exactly where she was…And what if she went crazy? Her mother had gone crazy, screaming her hopeless, mad scream, weeping for hours, for days…crying her head was splitting in two. Loretta had seen other crazy people, had seen how fast they changed into being crazy. No one could tell how fast that change might come” (p. 29).

And as the story progresses, we watch Loretta grow beyond her insecure adolescence into the confusion of marriage and motherhood.

I will introduce you to her eldest child, who Oates depicts with amazing sensitivity, warmth, violence, and curious states of consciousness. Let’s meet Jules.

Jules

Readers come to grips with the depth of Jules who we see grow up facing the complexity of his inner and outer worlds. He is good looking, caring, sometimes ambitious, and learns about love and hurt in searingly painful ways. Chronically afraid of being caught for desperate actions with little criminal intent beyond survival, readers fall in love with him, hope for him, struggle with him, and enter both his hopes and despair.

Only Joyce Carol Oates could depict such a remarkable young man fighting to figure out life.

Deeply in love in a way that the reader wants to fathom along with him, Oates creates the constant vibration of the dangers of loving, of making love, and of losing love in dramatically terrifying ways.

“‘ Jules, don’t leave me!’

‘It’s all right.’

Her cries were high, terrified, like the cries of ocean birds. He felt her turning into a wild, cruel bird. He felt her sinking and rising and sinking again in the frenzy of her own mind, unable to draw herself up, weighed down to insensibility. He wanted to turn his face away from her. But he kissed her instead, hungrily and wildly himself, in imitation of her passion and out of courtesy, to hide it from them both…What he had thought elegant in her was only her distance from him, a female distance. ..They were enemies” (p. 415).

Jules tries so exasperatingly hard to make a life for himself that a wild push of experiences spring him forward with hope and then fall, crashing down in disasters.

After facing the possibility of death due to a deeply misguided relationship,

“He was safe from his own past, kicked free of his own past…Jules had disappeared.”

But then, thinking he has escaped his troubles, at last, he is challenged by the race riots that devastate Detroit in 1967. He’s too lost in himself to capture this building up of tensions he’d always lived with that now took a grievous political turn. He’s faced death and has no intention of joining his peers in talk of assassinations, political deaths.

“‘ What is your opinion, Jules?’

“I don’t have any.’

“Who should we kill, Jules? If you had your finger on the trigger, who would you kill?’

“Nobody.’

“Why not?”

“Why? Why kill anybody? People die anyway, sooner or later…It wouldn’t change anything'” (p. 487).

Then he walks away from the agitated political schemes with a young woman. He steers her to his apartment and unlike the Jules we always knew, so careful with women, so loving, so kind, he has sex with her, with an unwilling and confused young girl, after which he says…

“‘ Once I thought it wouldn’t be possible to live without love, but it is possible, you keep on living. You always keep on living’

‘You what?…What?’

‘You always keep on living” (p. 498).

As a reader who has loved Jules, been with Jules desperate ups and downs, we now find ourselves perplexed, confused by this seeming change in his moral fiber, his long journeys searching for real love and even permanence. Is all that ending?

“Silence began to fill up inside him” (p. 498) …” the pinpoint of energy at its very center—Jules Wendall—became hard and bitter and useless, like a grain of sand or grit” (p. 499).

Has Jules finally at long last reached the limit of his capacity to drive himself forward with any positive aims in life?

“Jules had an unclear, sudden hallucination of beasts—transparent beasts in the space between himself and the kitchen doorway” (p. 500).

“He felt as if all the strength had drained out of him, dissipated into the air of this room and of other rooms adding up to his past…It was strange to Jules how familiar everything seemed, as if like the walk to and from his room, the entire world added up to a few sights and sounds that had to be used over and over again” (p. 501).

“He felt no energy to get up and go downstairs and face the street again. The air between himself and the door was opaque and dangerous, as if crowded with invisible shapes” (p. 503).

I will shortly leave Jules now in this state without venturing forward to the novel’s ending. That I leave for you.

“Everyone was struggling, climbing up, but Jules was sitting off to one side in a daze, happy, unhappy, not waiting. …What did that mean, to be a woman’s lover? What difference did it make? …He was like the weeds that grew to a height of three or four feet right through the sidewalk’s cracks, struggling upward but without cruelty or design, mindless and content. …They were permanent though they had no consciousness” (p. 506).

“He did not know what he wanted” (p. 509).

Conclusion

“Them” is broadly an epic about the white impoverished class of people in Detroit—the not “us” middle class and upper-middle class. To many, this book is making a political statement using the characters as composites of people of a certain social class.

But as brilliant as that assuredly is, and as timeless as that is, it is also just about people’s hopes and dreams, how they falter, sometimes succeed briefly and boldly courageously facing demons within and without themselves as they—that is some and in fact, many—move forward straining to continue to believe they can reinvent their lives only to discover they still live with their selves carrying “them” so deeply within just in new configurations and stages of life.

It is also a book about love—its meaning, its expression, its convulsive nature—that leaves us all wondering how to find it, what to do when it’s lost, and how to continue to grow to find its meaning over and over again.

The emotion connected with social tumult reverberates in this grand novel with the personal emotions borne by the individuals growing up it.

“Them” in that way is also ‘Us.’ No one is immune.

Once again, Joyce Carol Oates explores social class in American by disclosing the inner worlds of young Americans, this time migrant farmworkers who live in shanties constantly moving, trying to cope with precarious impermanence.

Oates rewrote this book because as an older writer reviewing her more youthful work, she decided she wanted to more deeply portray the complexity of the inner workings of her primary characters’ minds. She wanted us to be listening to each of their unique voices rather than expository narration. She most assuredly succeeds.

In her Afterword, she ends with this note: “to have, and not to be, is to have lost one’s soul” (p. 404). This theme is the essence of this epic novel. I will introduce you to her principal character.

Clara

Clara Warpole grows up to become Clara Revere. Beautiful, feisty, poor, deprived, and confused, she runs away as a young girl and meets two men who in turn change her life or perhaps I should say, help her find ways to try and satisfy her desperate desire for permanence, love, and security. With the first, she becomes pregnant with her son, Swan, without his father’s awareness.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. First, I’ll introduce young Clara?

“The teacher said, ‘What are you going to do with yourself?’

‘What?’ said Clara brightly.

‘What are you going to do? You?”…

“You mean me?’ Clara whispered.

‘Oh, you’re all—white trash’…

‘You shut up—you’re the same thing!’ Clara snarled…” (p. 47)

A little older, barely entering adolescence, she meets Lowry, an older man by Clara’s standards who, to her initial dismay, treats her like the child she still is.

She at first wants to view him in a sexual way though she doesn’t understand what her body is telling her. But instead, he washes her like a child humiliating her yet giving her the beginnings of a new sense of being cared for.

As readers, we want to love and fear Lowry with Clara as he comes in and out of her life. As she grows older, he’s a critical person for her by giving her a taste of a more hopeful self-reliant life. He’s protective, loving, and does not exploit her naivete though he surely could. But with this fascinating character, she’s met a man in his twenties who is still trying to find himself, not exactly the kind of guardian she needs, yet a powerful figure in her entrance into her expanding real world.

She felt love for Lowry spurred by her desperate helplessness but also came to hate him as he did the decent thing. “…he looked as if he had two parts to him, the outside part and the inside part that wanted to get out” (p. 164). Her complex longings made it immensely difficult for her to contend with him.

We spend a long time getting to know Clara in her youth due to Oates’ remarkable capacity to give Clara a voice that is penetrating, reckless, and bold. We are always rooting for her to make sound choices, which always leave us hanging, worrying about her safety and her future prospects.

The story unfolds dramatically as she mothers Swan, later to be called Steven. This highly intelligent son surpasses her abilities in many ways, but she’s unable to understand how he, like her, wants to figure out who he is and who he can become.

Oates weaves coming of age tales for both Clara and her son. Like complex wandering Lowry, who tries to protect and love Clara in different ways, she, too, tries to protect and give her son a better life than she had as a little girl. But when she meets the second major man in her life, Revere, a wealthy landowner, she creates a life for her son that he can’t quite ever make into his own.

Swan’s confusing adolescence isn’t understood by Clara, who is still making her own way in her world.

“At such times he [Swan] believed himself an individual in a dream not his own like one of those hapless voyagers of Edgar Allan Poe who made no decisions, were paralyzed to act, as catastrophes erupted around them” (p. 351).

Mother and son clash during his adolescence.

“‘ Tell me what I said. I must have made you mad, right?”

‘No, you didn’t make me mad.’

‘But you’re mad now? Because you have a girlfriend you have to turn against your mother?’

‘I haven’t turned against you,’ Swan said.’

‘Look around at me then. Why do you look so sad? What’s wrong?’

“I don’t know what’s wrong,’ Swan said helplessly…the sense of alarm and depression…was like a puddle of dark water moving steadily toward his feet'” (p. 360)

Oates remarkable talent in detailing the multiple states of mind Clara experiences with Lowry, Revere, and Swan enables us as readers to live inside her complex life, adore and fear for her son, and follow her rising and falling over and over along with her child who merits a full section of the novel devoted to him.

With raw, chilling, loving, and raging dialogue and narration, Oates depicts how cultures define people as they struggle endlessly to find themselves. This is literary fiction at its psychological best through prose that is spellbinding, terrifying, and compassionate all at once.

Short Story Collections

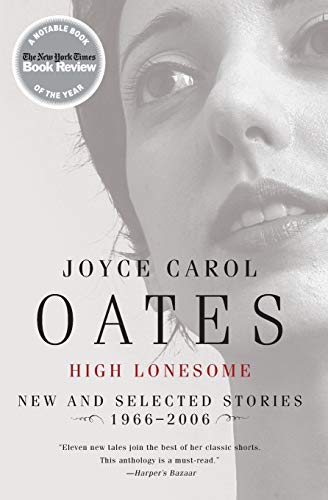

Reviewers of Oates relatively new collection of short stories in her volume, “High Lonesome: New and Selected stories 1966-2006” speak of the “edgy vitality and raw social surfaces” (Chicago Tribune) and “an uncanny gift of making the page a window, with something happening on the other side that we’d swear was life itself” (New York Times Book Review).

I also found the edgy rawness and the window into something tragic happening but was at first disappointed after reading Oates’ Novels to find as a reader in her very short stories I was getting a tragic slice of life, but just a slice and wanted more.

I wanted her to give me more of her unusual dialogue and metaphoric prose, so I could not just feel a glimpse of parent’s and teenager’s tragedies but also be able to try and understand them.

I will share two with you.

1. Spider Boy

In “Spider Boy” I meet a teenager whom I assume is bereft by the loss of his politician father, who is impeached and goes to prison. I also meet his mother, who is ashamed and wants to hide from the news reports. But who are they? I want to do more than look in their window.

I want to feel what it’s like to be part of that household but am not given a chance. I definitely feel the anguish and uncertainty and impermanence of their lives, but I’m unsure if that’s enough. Maybe it is, and that’s the point. The rest is left to the reader’s imagination.

2. The Fish Factory

Reading “The Fish Factory” left me with the same uncertain feeling. Of course, if your teenage daughter’s body is found in the woods, it’s a tragedy in a news report. But I want to get to feel whatever that young girl felt. I want to be bereft with her parents.

But Oates just gives me the report, so to speak, surely in her fine-tuned prose, but it lacks the depth of characterizations in various cultures she so remarkably lends us in her novels. Is that enough?

Notes

Surely, I could say, how much can this great author give us and demand of us as readers in only a few short pages of these very short stories but compared to my recent discussion of Daphne Du Maurier’s short stories, I regret to admit I find these particular Oates stories fall short.

For me, that is. Maybe not for you. My disappointment did not prevent me from persisting and reading more of other collections I will share with you. (Also, other stories later in this collection are longer, so there’s a lot more I could say about this collection, yet I’ll move on.)

My experience as a reader was more like I was given the great opportunity to read a great author’s notes about stories she planned to tell. I was taken by the notes but am left wanting a story!

I considered if I was reading the newer genre, Flash Short Stories, but they are generally a few paragraphs and have a beginning, middle, and end. Their poignancy gets to your gut like a knife—1,000 words max in about three minutes.

“For sale. Baby shoes. Never Worn” is flash fiction attributed to Hemingway.

What do you think of this version by another author, “Baby shoes for sale. Only worn once.”

They both strike a chord. In the second, my image is of a baby that is gone, so cannot wear them again. Horrible thought! But then I return to the supposedly Hemingway brief and feel even worse. Did the baby die before a present of his shoes could be worn?

In either case, you can see I’m sharply affected. I make up my own story in my imagination to fill in the blanks. What did your imagination lead to? However, I also did find an example of genuine flash fiction by Joyce Carol Oates on Google.

See how you feel after reading this:

“I kept myself alive!”

Keep that line in mind when I proceed to another of her collections. But for now, with this brief introduction to flash fiction, perhaps Oates in the particular collection discussed here is trying for something similar and, with that in mind, succeeding along those lines.

1. Soldier

In this tale about Brandon Shrank, Oates’ opening line could be flash fiction, but it’s only the beginning:

“They have advised me. It could be a fatal mistake, to open your mail” (p. 33).

I’m tempted to tell you right off why this line is so important, but I’ll resist because I want you to find out at the end of the story. So, I’ve given you a little hint.

Brandon is a young Caucasian fellow accused of murdering a young African American fellow. He will state his case at first in a way that’s a story about saving his life. Given our political times today and, of course, for decades, this is most relevant.

We come to feel with Brandon for sure. He’s repeatedly told not to view any social media or volumes of mail sent his way. But for one moment at least, he does not hold back from the words:

“Racist. Murderer…” (p. 44).

Like in her novels, Oates gets us to enter Brandon’s body and mind:

“My heart is beating hard, there is the ringing in my ears that comes with dizziness. I know that I should not be seeing such things, it is what my lawyer has warned against” (p. 44).

“It is not just that I have been warned not to speak of the shooting. Not just that I have been warned not to speak of that day in my life, the decision I made, or presumably made, when I entered my uncle’s kitchen and took away his .45 caliber police service revolver without telling him, and concealed it in my waterproof polyester jacket; when I carried the gun against my heart for how many hours, how many minutes of mounting excitement, as one might feel carrying a bomb strapped around his waist that is set to explode at an unknown time… I don’t know how to speak of what happened—what happened to me—not what I did” (p. 63).

I’ve only mentioned what Brandon did, not what he was actually faced with, according to his initial report. With a short story, I cannot reveal too much. But clearly, here we see Oates frame a well-polished story that will leave you at the end wondering about a great deal.

She has masterfully engaged your mind with Brandon’s mind, opened up many questions about not only what happened to Brandon but about the most contemporary phrase, “Black Lives Matter,” and turned it all on itself to ponder, fear, question, maybe take sides for a few pages and then question even more, and…

Please read on by yourself!

2. Gun Accident

In 76 pages, Oates takes the reader on a treacherous confusing ride about life and death, fear and supposition, guilt and innocence, family relations, and so much more.

Clearly, this time you will get into the protagonist’s mind, share her emotions, and discover your own as the plot twists and turn in the most unexpected ways because Oates sets up the reader to see a young girl only in one way.

The reader feels she is reading the coming-of-age story of an adolescent girl, forgetting this is a collection of horror stories until—the unexpected disarms and alarms you only to reach the lack of closure at the end.

Postscript

I can only share with you the admiration and tumult I experience reading Oates novels and short stories. She is indeed a stunning artist, a literary genius, a must-read for any aspiring writer or cultivated reader.